Cyber, Tech and Data Risk Report – Issue 7, March 2024

We are delighted to share Issue 7 of our Cyber, Tech and Data Risk Report – our wrap-up of relevant news for the first quarter of 2024 for insurers, brokers and their customers doing business in Australia and New Zealand in the cyber, tech and data fields.

In our March issue, we cover the Australian Government’s plans to fast-track reforms to the Privacy Act in response to doxxing, the commencement of the consultation phase of the government’s 2023-2030 Cyber Security Strategy, the latest OAIC notifiable data breaches report, leadership changes in Australia’s key privacy and cyber regulatory roles, the question of whether ‘data goods’ can be the subject of a bailment, and provide an update on OAIC regulatory action in response to data breaches.

We also delve into global developments including the political agenda when it comes to the use of AI in government decision-making, Australia and the UK enhancing their online safety cooperation with the co-signing of an MoU, and the rise, fall and resurgence of LockBit.

If you would like to discuss anything covered in these articles, please reach out to a member of the team.

The Federal Government has signalled its plans to progress reforms to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) – the first announcement of its kind in 2024.

In February 2023, the Government released the Privacy Act Review Report, which set out 116 privacy reform proposals for public consultation. In September 2023, a response paper was released, providing insight into which of the reform proposals the Government agrees with and intends to focus on, although the timing of legislative changes in response was unclear. We summarise that paper here.

Earlier this month, the Government released a consultation paper, seeking public submissions on plans to enhance privacy reforms and civil remedies. The following were flagged as priorities (amongst other things):

- a new statutory tort for serious invasions of privacy

- giving individuals greater control and transparency over their personal information, including the introduction of new or strengthened individual rights to access, object, erase, correct, and de‑index their personal information, and

- progressing other privacy reform proposals contained in the Privacy Act Review Report that bring the Privacy Act into the digital age, uplift protections, and raise awareness of obligations for responsible personal information handling.

The consultation paper comes in response to the Government announcing plans to utilise the Privacy Act reforms to crackdown on ‘doxxing’. Doxxing has been defined by the Government as the “targeted and malicious release of personal information without permission”. The Prime Minister told the media that the Government would fast-track privacy legislation amendments as part of its plans to prevent doxxing.

Whether broader privacy reform proposals are earmarked to be progressed during the process is currently unknown.

The Australian Information Commissioner met with the ombudsman and their New Zealand counterparts in early March 2024. A key topic of discussion was the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in government decision-making, and the consequences for people seeking to exercise their right to access information.

Challenges flagged included outsourcing technology, oversight of systems to ensure they operate as intended, and difficulties in obtaining multiple inputs to datasets that could alter a decision over time.

AI has been on the agenda for governments globally, with the United Kingdom Government recently announcing a range of measures to progress AI investment and regulation. Our colleagues at DAC Beachcroft discuss this further here.

The last six months has seen a marked uptick in the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s (OAIC) regulatory activity in response to data breaches. Further to our commentary on the key decisions and investigations of 2023 in Issue 6 of our Cyber, Tech and Data Risk Report, we set out some recent developments below.

Currently, the OAIC’s investigations into Medibank and Optus remain ongoing, running simultaneously with class actions from individuals affected by the respective breaches. On 22 February 2024, the Federal Court dismissed an application by Medibank for an injunction to halt the OAIC’s investigation until the resolution of the class action proceedings (read more). It remains to be seen whether Medibank appeals the decision.

On 21 February 2024, the OAIC commenced an investigation into the data breach suffered by HWL Ebsworth Lawyers (HWLE) in mid-2023 (read more). Specifically, the OAIC will investigate HWLE’s practices in relation to the security and protection of personal information held, as well as the notifications made to the individuals affected by the breach.

While we await the outcome of these actions, they are certainly consistent with the more active approach we have observed being taken by the OAIC in exercising their regulatory powers, which we expect will continue throughout 2024.

On 22 February 2024, the OAIC released its report on the Notifiable Data Breaches (NDB) scheme for the period from July to December 2023 (the Report). The Report provides a statistical overview on reported breaches, and key insights into the OAIC’s priorities in administering the scheme.

To recap, the NDB scheme requires entities subject to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) to notify the OAIC and any affected individuals when a breach is likely to result in serious harm to any individual whose personal information is involved.

Key findings

The report lists the following key findings for the July to December 2023 period:

- There has been a 19% increase in the number of notifiable breaches, totalling 483.

- Malicious or criminal attacks remained the leading cause (67%) of data breaches.

- The health and finance sectors remained the top reporters of data breaches.

- Most data breaches involved contact details (88%), including name, home address and phone number. The next is identity information (63%), including date of birth, passport details and government identifiers. Following is health information (41%), which surpassed financial information from the previous period.

- The time taken to identify a data breach varied depending on the type of breach. Human error breaches were identified the quickest at 71% in 10 days, followed by malicious or criminal attacks at 61% in 10 days. System fault breaches were identified the slowest at 53% in 10 days.

- Compromised or stolen account credentials caused most (25%) of the data breaches in Australia for the July to December 2023 period.

OAIC priorities

The latter half of 2023 saw the OAIC cracking down on entities failing to comply with requirements under the NDB scheme. In October 2023, the Information Commissioner handed down determinations against Datateks Pty Ltd and Pacific Lutheran College for their handling of data breach events.1 The determinations focussed on the entities’ failure to conduct an ‘expeditious’ assessment and ordered both entities to promptly develop a considered data breach response plan.

The OAIC has more recently demonstrated their willingness to go further and seek a financial penalty for such breaches. In November 2023, civil penalty proceedings were commenced in the Federal Court against Australian Clinical Labs Limited (ACL), following an investigation into its privacy practices stemming from a data breach incident in February 2022. The Commissioner alleged that, in the period prior to the cyber incident, ACL failed to take reasonable steps to protect personal information held, and that following the incident, ACL failed to conduct an expeditious assessment and notify the Commissioner as soon as practicable. The matter is currently before the Federal Court, who may impose a civil penalty of up to $2,220,000 for each contravention (notably under the previous penalty regime).

Clearly, the OAIC has identified the security of personal information as a regulatory priority and is taking a stringent and active approach to ensuring regulatory compliance.

Other key takeaways from the Report include:

- ensuring effective data retention policies are in place which comply with obligations under Australian Privacy Principle 11.2

- remaining vigilant in view of the prevalence of large-scale data breaches that involve the use of malicious or criminal tactics – notably, the use of compromised credentials by attackers to gain access to business systems

- the need for effective IT security measures in place to prevent attacks – the Report directs entities to the Australian Cyber Security Centre’s recommendations which outline the Essential Eight cyber security strategies to defend against cyber threats, and

- when engaging third party cloud or software providers to handle personal information, to ensure contractual agreements cover retention and breach obligations in the event of an attack. Effective due diligence on the provider’s ability to protect the systems that hold personal information, and setting clearly defined expectations for reporting suspicious activity, is key.

[1] Datateks Pty Ltd (Privacy) [2023] AICmr 97; Pacific Lutheran College (Privacy) [2023] AICmr 98.

February 2024 saw changes in leadership in Australia’s key privacy and cyber regulator roles.

Carly Kind commenced as Australia’s new Privacy Commissioner on 26 February 2024. Carly takes over from former Information and Privacy Commissioner Angelene Falk, who has moved into a standalone Information Commissioner role. Ms Kind comes to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner following a career as a lawyer advising industry, government and non-profit organisations on digital rights, technology, privacy and human rights. She is a former director of the Ada Lovelace Institute, who manage research on the legal and ethical development of data-driven technologies such as AI.

Also on 26 February 2024, Lieutenant General Michelle McGuinness commenced as the National Cyber Security Coordinator. She is the second person to take the role, after inaugural coordinator Air Marshall Darren Goldie was recalled late last year. Lieutenant General McGuinness has served in the Defence Force for 30 years in tactical, operational and strategic positions. Since 2021, she has served in the United States Defense Intelligence Agency, leading a number of interagency intelligence efforts.

With privacy laws and cyber strategy initiatives expected to be progressed, these new appointments kick off what looks to be an important year in the data and digital landscape.

On 20 February 2024, Australia and the United Kingdom (Participants) co-signed the Online Safety and Security Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), signifying bilateral cooperation to deliver online safety and security policy initiatives to support individuals and businesses.

While not legally binding, the MoU establishes a framework for the Participants to implement policy initiatives and outcomes to protect online users in a way that protects their privacy, but does not limit their freedom of expression.

The MoU will build on existing regulatory regimes, including the UK’s Online Safety Act 2023 and Australia’s Online Safety Act 2021.

Australian Minister for Communications, the Hon Michelle Rowland MP, said in a statement:

“Online safety is a shared, global responsibility. We must be proactive in ensuring that our legislative frameworks remain fit-for-purpose, and continue to evolve as new harms emerge”.

The initial focus and scope of the MoU is on a number of policy areas, including harmful online behaviour, user privacy and freedom of expression, lawful access to data, encryption, countering foreign interference, online scams/fraud, information sharing around regulation, and the impact of new, emerging and rapidly evolving technologies (such as artificial intelligence models).

There are ten joint actions flagged under the MoU, notably:

- Regulation and enforcement, including increased cooperation between the Participants’ law enforcement agencies and regulators, to enhance investigative and enforcement activities. This could mean regulators such as the OAIC become more actively involved in joint data breach investigations.

- Tech industry accountability, with a commitment to cooperation between global technology companies to increase consistency in cyber security in areas such as end-to-end encryption, and enhanced technology to protect the privacy of individuals.

- Countering foreign interference, with a bilateral commitment to reducing such interference through information sharing. This could improve the ability of Participants to track down entities conducting cyber attacks.

The MoU is another step in the Australian Government’s objective to combat rising cyber security and online threats.

Hot on the heels of the Government’s 2023-2030 Cyber Security Strategy (Strategy) released on 22 November 2023, and the associated 2023-2030 Australian Cyber Security Action Plan (Action Plan), the consultation phase has now commenced. On 19 December 2023, the Government released a consultation paper to seek views on proposed legislative reforms and measures to give effect to the initiatives and measures in the Strategy and the Action Plan. As the effective implementation of the Strategy is openly dependent on public and private sector co-leadership, these consultation measures represent an important step in achieving the Government’s stated aim of making Australia a world leader in cyber security by 2030. The consultation paper outlines two areas of proposed legislative reform – omissions from current cyber regulatory frameworks and amendments to the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (Cth) (SOCI Act).

Part 1

Part 1 (Measures 1 to 4) of the consultation paper seeks industry opinion on proposed legislative options to address gaps in current regulatory frameworks, as identified in the Action Plan, which outlined six ‘Shields’ that the Government will focus on to make Australia a leader in cyber security by 2030.

These Measures are:

- mandating a security standard for consumer-grade Internet of Things technology to incorporate basic security features by design and help prevent cyber attacks on Australian consumers. We see this as an important first line of defence to consumers who are the most vulnerable to cyber threats.

- creating a no-fault, no-liability ransomware reporting obligation to improve collective understanding of ransomware incidents across Australia. Whilst we welcome the Government’s adoption of mandatory ransomware reporting obligations, the Government must also be careful not to overburden SME businesses with regulations that could be expensive and administratively burdensome to follow at a time when resources and focus will likely be on containing or recovering from a cyber incident.

- creating a ‘limited use obligation’ applicable to the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) and the National Cyber Security Coordinator as to information voluntarily disclosed by impacted organisations during a cyber incident in order to encourage industry to continue to collaborate with the Government on incident response and consequence management. We support this measure on the basis that it is likely to facilitate more extensive and open cyber incident reporting to the ASD and Cyber Coordinator by organisations impacted by a cyber incident.

- establishing a Cyber Incident Review Board (CIRB) to conduct no-fault incident reviews and share lessons learned to improve national cyber resilience. We consider that the new CIRB is likely to improve national cyber resilience in Australia, but the Government must consider the post-incident review process, particularly where it may impact the ongoing operations of the organisation recovering from an incident.

Part 2

Major recent cyber security incidents impacting critical infrastructure, such as the Optus breach in 2022, illuminated gaps in the SOCI Act – the primary piece of legislation regulating Australia’s critical infrastructure – that prevented effective planning and consequence management. Industry stakeholders have called for greater assistance from the Government in quickly handling the potentially dire effects of cyber incidents in critical infrastructure. In response to these calls, the Government is seeking to enhance protections over critical infrastructure by improving the clarity of security standards, the consistency of application of obligations, and the coordination of incident response.

Part 2 of the Consultation Paper asks for feedback on five proposed measures that the Government seeks to achieve through reform to the SOCI Act:

- increasing security over critical infrastructure data storage systems that store ‘business critical data’. This expansion of critical infrastructure security obligations should better protect Australians from the potential detrimental consequences of cyber incidents impacting critical infrastructure.

- introducing a directions power for the Minister for Home Affairs to assist in managing the consequences of incidents affecting critical infrastructure. We consider that a legislated governmental power for the consequence-management of significant critical infrastructure incidents would be a welcome addition to the cyber security regulatory framework.

- simplifying information sharing in crisis situations. We consider that this should promote a more timely and comprehensive response for critical infrastructure entities to respond to high-risk cyber incidents under the provisions of the SOCI Act.

- providing review and remedy powers to enforce critical infrastructure risk management obligations. Whilst we consider that the proposed SOCI Act enforcement power in relation to certain deficiencies should be an effective means of increasing cyber maturity and accountability of critical infrastructure entities, we also favour a ‘carrot’ approach over the ‘stick’ approach called for by critical infrastructure entities, requesting increased Government support in managing and mitigating the consequences of cyber incidents.

- consolidating telecommunication security requirements under the SOCI Act. We consider this consolidation will enhance Australia’s critical infrastructure and promote our cyber security ecosystem by aligning obligations for telecommunication entities with other critical infrastructure sectors.

Watch this space for further developments as the consultation process for the implementation of the Strategy and Action Plan initiatives rolls on.

Takedown

On 20 February 2024, a joint international law enforcement taskforce including agencies from the United States, United Kingdom and Australia announced the successful takedown of the LockBit ransomware group.

LockBit was one of the most common ransomware variants, and since first entering the scene in 2019, have received more than $120 million in ransom payments from over 2,000 victims.1 The enforcement action is one of the largest and potentially most significant ever taken against a cybercrime group.

The takedown is significant as it is the first time that law enforcement have been able to take full control of a major ransomware gang’s infrastructure and operations.

The taskforce, named ‘Operation Cronos’, conducted a 2-year investigation in the leadup to the shutdown, where they took control of LockBit’s main leak site and released a decryption tool allowing victims to recover files, amongst other activities. At least three affiliates connected to LockBit were arrested, and more than 14,000 rogue accounts responsible for data exfiltration have been closed.2

Notably, the taskforce discovered that LockBit were holding on to data they had pledged to delete after receiving a ransom payment.

The takedown comes as law enforcement agencies around the world have taken a progressively more aggressive approach to cybercrime groups.

Our colleagues at DAC Beachcroft discuss further details of the takedown here.

Resurgence

On February 26 2024, LockBit made a statement announcing its resurgence, and have since resumed operations at a different dark web address. At least 12 victims have been added to the new site, however, this notably does not refer to victims prior to the takedown. They blamed IT vulnerabilities and ‘personal negligence and irresponsibility’ for the takedown, and have offered a financial reward to anyone that can hack their new system.

The resurgence supports the notion that large-scale ransomware groups are capable of regeneration following law enforcement activities. This is not dissimilar to the actions of the ALPHV/BlackCat and Hive groups, which were dismantled by law enforcement and then reborn shortly thereafter.

Key takeaways

- Law enforcement actions are having an effect in disrupting (albeit temporarily) ransomware groups.

- Threat actor groups have the capability of reforming or utilising other methods to cause harm from cyber incidents.

- Payment of a ransom is not a sufficient guarantee that a threat actor will delete the data they have stolen. Organisations should consider their preparation and response practices to manage the risks of cyber incidents, including with a cyber incident response plan.

- Cyber insurance can play an important role in minimising the extent of harm and costs incurred from a cyber incident, allowing access to experts in areas including legal, forensics, threat intelligence and communications.

[1] https://techcrunch.com/2024/02/21/six-things-we-learned-lockbit-takedown/?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAEh33N2NF5xEG_hFSls1O-kP4N0PIGzRZtJaB4fk6zgVx4yGySX5lUNzO5qSiOrzXtMtSm17noKFSQuWfcK4t0AYOP9d3Zex-Q-GaVhiLIEbyIjPkLFGNRi3bHLSHumoqL1wBhp6364cNCYrCg9p2yGwzjTIZihElaDWkoqfbtZt

[2] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-and-uk-disrupt-lockbit-ransomware-variant

As claims against technology professionals increase, particularly in relation to cyber incidents, we have seen plaintiffs advancing modern day interpretations of traditional causes of action. One example is where plaintiffs allege that a bailment relationship exists between managed / cloud services providers and their clients in respect of data hosting / storage.

Although the question hasn’t authoritatively been decided by an Australian court, the UK case of Your Response Ltd v Datateam Business Media Ltd [2015] QB 41 casts doubt on the proposition that data can be the subject of a legal bailment.

Facts

Your Response hired Datateam to manage their database. Your Response terminated the contract and Datateam refused to provide them access to the database until they paid outstanding monies owed under the contract.

Issues

The essential elements of bailment are:

- the delivery of the exclusive right of possession by the client

- the voluntary assumption of possession by the bailee

- an assumption of the responsibility by the bailee to keep the goods safe, and

- the obligation to return the thing bailed.

The key question for determination was whether ‘data goods’ could be the subject of a bailment.

Decision

The England and Wales Court of Appeal (EWCA) held that because it is not possible to take possession of an intangible, it is impossible to have a common law artificer’s lien over information in a database. Moore-Bick JA, with whom the other two justices agreed, made the following observation:

“Although an analogy can be drawn between control of a database and possession of a chattel… the two are not the same. Possession is concerned with the physical control of tangible objects; practical control is a broader concept, capable of extending to intangible assets and to things which the law would not regard as property at all.”

The EWCA held that you cannot possess something which is intangible. Since data is intangible, and possession is an essential element of bailment, that data could not be the subject of a bailment.

Moore-Bick JA made some other observations which may be instructive to an Australian court:

“Although the contract in the present case contained no express provision for the defendant to have access to the data, neither did it contain any provision, express or implied, excluding him from it, and the fact that the claimant did in fact make access to it freely available by the provision of a password is in my view inconsistent with the conclusion that he was in fact exercising the kind of exclusive control that would equate to the continuing possession required for the exercise of a lien…

the parties to a contract of the kind under consideration in this case are free to make express provision for their rights and obligations on termination of their relationship, and an extension of the right of self-help is to that extent less justifiable”.

Moreover, Floyd LJ stated: “Whilst the physical medium and the rights are treated as property, the information itself has never been”.

Although the decision may be persuasive to an Australian court, it would of course be open to an Australian court to resolve the question differently. Indeed, Moore-Bick JA acknowledged the force in Your Response’s arguments as follows:

“In my view there is much force in their analysis, which, if accepted, would have the beneficial effect of extending the protection of property rights in a way that would take account of recent technological developments. However, to take the course which they propose would involve a significant departure from the existing law in a way that is inconsistent with the decision in OBG Ltd v Allan. That course is not open to us – indeed, it may now have to await the intervention of Parliament.”

A third category of things?

Counsel in Your Response suggested that intangible assets that are not choses in action could constitute a third form of personal property that is neither in action nor possession. This proposition has long been rejected at common law: “According to my view of that law, all personal things are either in possession or in action. The law knows no tertium quid between the two”.1

The issue is illustrated by issues arising in relation to cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency is neither a chose in action or a chose in possession – it is merely code (a token), and is not a legal claim, i.e. has not created any legal property right in respect of it, even though it is a valuable asset. Bitcoin behaves like a chose in possession but has no physical existence (i.e. you can steal it in a way that you cannot steal contractual rights).

Consequently, the UK Law Commission has proposed establishing a third category of personal property.2 A thing will fit within this category if it:

- is composed of data represented in an electronic medium

- exists independently of persons and independently of the legal system, and

- is rivalrous.

Cases are having to deal with this on a case-by-case basis, and they are not asked to directly decide about whether the object is property for all purposes / limited purposes.

For example, the New Zealand High Court held that crypto was capable of being held on trust – to establish that things are capable of being held on trust, you must be saying that legal rights attach to them, however, the full extent of this finding is not clear.3

The status of digital assets – such as cryptocurrencies and customer data – is likely to become an emerging legal issue as businesses continue to adopt information technology in their practices and handle greater amounts of customer data. Coupled with the emerging use of artificial technology to conduct business faster, it is likely that further case law will arise regarding this issue in the future.

[1] Colonial Bank v Whinney (1885) Ch D (Fry LJ).

[2] UK Law Commission, Digital Assets: Summary of final report (2023) and Ch 3 ‘A “third” category of thing to which personal property rights can relate’, Digital assets: Final report (2023), both available at https://lawcom.gov.uk/project/digital- assets/

[3] Ruscoe v Cryptopia [2020] NZHC.

Cyber, Tech and Data Risk Report – Issue 6, December 2023

We’re delighted to publish Issue 6 of our Cyber, Tech and Data Risk Report – our wrap-up of news for the second half of 2023 for insurers, brokers and their customers doing business in Australia and New Zealand in the cyber, tech and data fields.

In our December issue, we cover a number of developments in Australia including legal privilege of forensic reports, the increasing number of data breach class actions, the government response to the Privacy Act Review Report, amendments to the PPIP Act, the proposed mandatory data breach notification scheme in Queensland, OAIC’s legal action against Australian Clinical Labs for cyber breach delay, and cyber insurance recoveries for subrogation claims.

For New Zealand, we cover the introduction of the Privacy Amendment Bill 2023, changes to the government’s approach to dealing with cybercrime, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC)’s project on privacy rights for children and young people and the OPC’s guidance on the use of AI.

If you would like to discuss anything covered in these articles, please reach out to a member of the team.

Australia

A timely reminder about the privilege status of the forensic investigation report Optus obtained from Deloitte relating to the September 2022 cyber-attack was delivered by Beach J in the Optus class action last month – see the judgment in Robertson v Singtel Optus Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1392.

While Beach J did not find that mere reference to the report in press releases by Optus would have resulted in a waiver of legal privilege, the issue was rather that the report was never privileged to begin with because the evidence did not establish the dominant purpose was for the provision of legal advice. In his judgment, His Honour was critical of what he characterised as “endeavours to cloak the Deloitte review with legal professional privilege” after work had already commenced.

In his decision, Beach J was clear that reports which have multiple purposes will not be protected by legal professional privilege. In reaching that decision, he considered the various statements, both external (via press releases) and internal (including board material) which showed that the report had been commissioned in advance of the retainer of Deloitte by Optus’ external lawyers. That ultimately led to his conclusion that he could not be satisfied that the dominant purpose for the report was the provision of legal advice, despite the privilege protocol put in place by Optus’ external lawyers in the formal retainer. Interestingly, Beach J found that the reference to the retention of Deloitte in press releases would not have amounted to a waiver of privilege, if it had been established that the report was privileged in the first place. Optus may still appeal the decision and there is also the potential for it to make limited claims for privilege over parts of the report. In a case management hearing following the decision, Beach J indicated that Optus could propose redactions to the report to protect information that it maintains is privileged. Regardless of the ultimate outcome in relation to this report, the decision is a good reminder for organisations of some key issues to keep in mind when commissioning forensic investigation reports after a cyber incident:

- Be clear at all times on the purpose of reports which are retained in response to cyber incidents.

- Reports need to be for the dominant purpose of the obtaining legal advice – that does not mean the report cannot be used for other purposes but, if there are dual purposes, then the privilege status may be called into question.

- It is critical that protocols for the protection of the confidentiality of the report are established at the outset.

- Legal review of external statements is recommended to guard against waiving privilege.

In recent years, Australia has seen a surge in class action lawsuits stemming from data breach incidents, with businesses facing mounting legal challenges and reputational damage.

This article delves deep into the intricacies of data breach class actions, dissecting the legal framework, its implications for businesses, and the potential road ahead.

Read the full article here.

The Australian Government’s response to the Privacy Act Review Report (which was released on 16 February 2023, and set out 116 privacy reform proposals for public consultation) was released on 28 September. W+K’s Cyber team has summarised the Government’s response, outlining the five key areas with which it agrees with the Report’s proposals. The release of the priority areas and response by the Government sets some clear indications that the Privacy Act amendments are likely to progress imminently over the coming months.

Read the full article here.

On 28 November 2023, amendments to the Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 (PPIP Act) came into effect, with the most notable change requiring NSW public sector agencies to notify the New South Wales Information and Privacy Commission (NSW IPC) of eligible data breaches on a mandatory basis (MNDB Scheme), replacing the previous voluntary scheme.

The amendments were first passed in November 2022, with agencies provided a 1 year grace period to comply before the changes came into effect.

The MNDB Scheme now closely aligns with the Federal Privacy Act notifiable data breach scheme and requires agencies to notify the IPC and affected individuals where there has been unauthorised access, disclosure or loss of personal information held by an agency which is likely to result in serious harm. Agencies are required to take all reasonable steps to complete their assessment within 30 days after first becoming aware of the incident.

There are several other key amendments to the PPIP Act:

- Expansion of the definition of ‘public sector agency’ to include NSW state-owned corporations. This means that NSW state-owned corporations will be required to comply with the PIPP Act and the new MNDB Scheme, including for example Hunter Water, Sydney Water and Port Authority NSW.

- The MNDB Scheme also requires agencies to satisfy other data management/transparency requirements, including to have a publicly accessible data breach policy, maintain an internal data breach incident register, and update their existing Privacy Management Plans.

- The Commissioner’s powers have also been expanded to cover the new MNDB Scheme, including directing agencies to provide certain information to the Commissioner, recommending agencies to notify individuals of a suspected data breach, and accessing relevant premises to observe agency’s data handling policies and procedures.

A mandatory data breach notification scheme (Scheme) is one step closer for Government agencies in Queensland.

The Queensland Government has recently introduced the Information Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2023 (Queensland) to Parliament to establish the Scheme, which would require the Office of the Information Commissioner (Queensland) and affected individuals to be notified of eligible data breaches that would likely result in serious harm.

The requirements of the Scheme are materially similar to the Commonwealth’s Notifiable Data Breaches Scheme under the Privacy Act 1988 (Commonwealth Act) – and this is not the only area where Queensland is seeking to align with the Commonwealth. The Bill also proposes that Queensland move to a single set of privacy principles that align with the Commonwealth Act’s ‘Australian Privacy Principles’ (in contrast to the current, separate set of ‘Information Privacy Principles’ for most personal information, and ‘National Privacy Principles’ for health information). Public consultation on these reforms was sought early last year.

The timing of the Bill is poignant, just weeks after an announcement by the Commonwealth Government to progress its review of the Commonwealth Act. In a media release, the Queensland Government considers the Bill to be a ‘stepping stone’ for further reform following any legislative change arising from the Commonwealth Act review.

Should the Bill pass, Queensland will become only the second state to introduce a mandatory data breach notification scheme, behind New South Wales. Such a scheme has been on the agenda for the Government for several years, following recommendations arising from several public sector culture reviews – most notably the Coaldrake Review.

While mandatory, the Scheme would only relate to data breaches involving Queensland public sector agencies and connected entities. Private sector organisations based in Queensland will continue to be subject to the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), where applicable.

The OAIC commenced civil penalty proceedings in the Federal Court against Australian Clinical Labs (ACL), following an investigation into ACL’s privacy practices which arose as a result of a data breach suffered by ACL in February 2022. This is the first time that proceedings have been commenced for, amongst other things, delay in notification arising from a data breach. Read more.

If the Federal Court finds there have been serious or repeated interferences with privacy in contravention of section 13 of the Act, ACL could face civil penalties of up to $2.2 million for each contravention (the incident occurred prior to the amendments made to the Privacy Act in December 2022 (under the Privacy Legislation Amendment (Enforcement and Other Measures) Act 2022), where the penalty provision was revised to $50 million).

The investigation follows a February 2022 data breach of ACL’s Medlab Pathology business, which resulted in unauthorised access to personal information and health information in excess of 100,000 individuals, with some of it being posted on the dark web.

The OAIC alleges that from May 2021 to September 2022, ACL contravened section 13G of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (‘Act’) through:

- breaches of Australian Privacy Principle (‘APP’) 11.1(b), which requires an APP entity to take such steps as are reasonable in the circumstances to protect personal information

- contravention of section 26WH(2), which requires an APP entity to carry out a reasonable and expeditious assessment of whether there are reasonable grounds to believe that the relevant circumstances amount to an eligible data breach and to take all reasonable steps to ensure that the assessment is completed within 30 days, and

- contravention of section 26WK(2), which requires an APP entity to notify the Australian Information Commissioner of an eligible data breach as soon as practicable after the entity is aware that there are reasonable grounds to believe that there has been an eligible data breach.

The court proceedings instituted here by the OAIC against ACL is the first of its kind and a timely reminder to APP entities regarding steps taken after any data breach around the need to expeditiously assess whether an EDB has occurred, as well as ensure that timely notification is made to any impacted individuals. Additionally, organisations found to have breached these provisions of the Act could face much steeper penalties in the future under the amended provisions of the Act.

On 13 November, ASIC released the results of its recent cyber pulse survey into the cyber capabilities of corporate Australia. The survey identified significant cyber gaps, in particular that many organisations are still being reactive rather than proactive when managing their cybersecurity, as well as a lack of sufficient control and oversight over third party or supply chain risks (presenting easy access to threat actors into organisations’ systems and networks). See the full results of the ASIC pulse survey here.

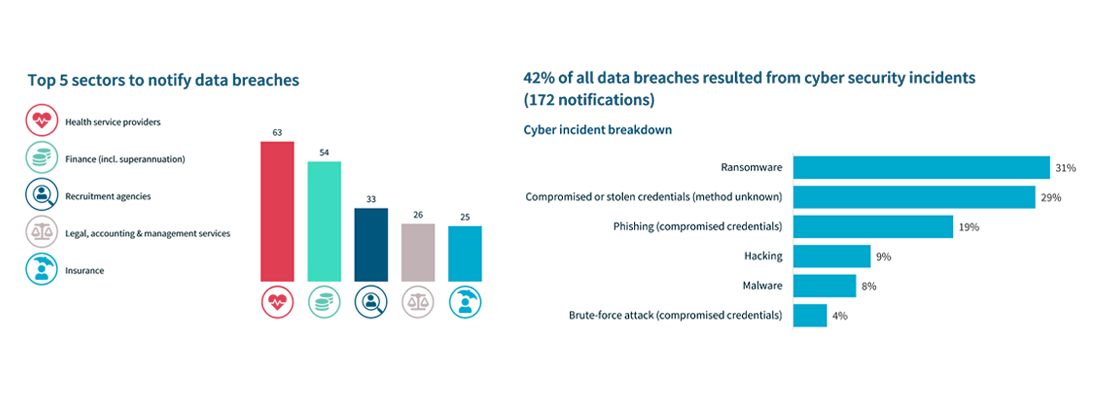

OAIC notifiable data breaches report for January – June 2023 released:

- January to June 2023 saw 409 data breaches reported to OAIC.

- Cybersecurity incidents were the source of 42% of all breaches.

- The top three cyber-attack methods were:

- ransomware, which accounted for 31%

- compromised or stolen credentials for which the method was unknown, which accounted for 29%, and

- phishing, which accounted for 19%.

Of relevance for entities that suffer eligible data breaches, the OAIC has cautioned APP entities against relying on the presumed motivations of threat actors and absence of evidence of unauthorised access when assessing cyber incidents:

“Reliance on these factors can adversely affect the accuracy of a data breach assessment. The OAIC also encourages entities to:

- Take a cautious approach. If an entity suspects a data breach has occurred but is unable to eliminate that suspicion quickly and confidently, the entity should consider proceeding on the presumption that there has been a data breach. Notification obligations are triggered once there are reasonable grounds to believe that an eligible data breach has occurred. Conclusive or positive evidence of unauthorised access, disclosure or loss is not required for an entity to assess that an eligible data breach has occurred.

- Consider all relevant factors and risks of harm. Entities need to assess a range of relevant factors, when assessing the likelihood of serious harm (s 26WG). Given the objective of the scheme is to promote notification, entities’ assessments should weigh in favour of notifying the OAIC and affected individuals.

- Focus on unauthorised access. Given the clear risks posed by exfiltration, the OAIC appreciates that initial priority may be given to assessing exfiltrated data and notifying individuals to whom it relates. However, an eligible data breach can occur based on unauthorised access alone and individuals’ data can be stolen by less traceable means, such as screenshots. Therefore, entities should not rely on data exfiltration as the determinative factor for deciding whether an eligible data breach has occurred. Entities need to consider all the information that was accessed by a threat actor, or the information that was accessible to them.”

In November 2023 the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) released its findings from the 2022-23 Financial Year https://www.cyber.gov.au/about-us/reports-and-statistics/asd-cyber-threat-report-july-2022-june-2023

The ASD responded to over 1,100 cyber security incidents from Australian entities. Of those, 143 related to critical infrastructure and approximately 10% included ransomware. Millions of Australians had their personal information stolen and published on the dark web, because of significant data breaches

Statistics

- Average cost of cybercrime per report up 14%

- Small business: $46,000

- Medium business: $97,200

- Large business: $71,600

- Cybercrime reports up 23%

- Calls to the Australian Cyber Security Hotline up 32%

- Top 3 cybercrime types for individuals:

- Identity fraud

- Online banking fraud

- Online shopping fraud

- Top 3 cybercrime types for businesses:

- Email compromise

- Business email compromise fraud

- Online banking fraud

ASD’s ‘Essential Eight’ cyber security mitigation strategies

- Application control

- Patch applications

- Configure Microsoft Office macro settings

- User application hardening

- Restrict administrative privileges

- Patch operating systems

- Multi-factor authentication

- Regular backups

The Australian Government released the 2023-2030 Australian Cyber Security Strategy on 22 November 2023. A summary and commentary of each shield is available below.

While many in the insurance industry will be familiar with subrogated recoveries, until recently there has been little appetite to pursue recovery actions in Australia for cyber claims.

We are now seeing a growing interest from insurers to pursue subrogated recovery claims against technology professionals in respect of ransomware, data exfiltration and system downtime, which are said to be attributable to failures by external technology providers.

This newfound desire is understandable where the Australian Signals Directorate has indicated that it receives on average a report of cybercrime every six minutes1, often leading to significant expenditure for insurers for first and third-party losses, forensic investigation costs, network restoration, ransom payments, regulatory penalties and business interruption.

Against this backdrop, it is unsurprising that insurers are increasingly looking to explore their own subrogation rights to recoup their losses from those whose acts or omissions can be said to have caused the incident. Subrogation can be an effective means of holding responsible parties accountable and, in turn, helping to lessen the financial burden on the insurer.

While there is an increased appetite, there is not yet an established body of caselaw in respect of these claims and, accordingly, subrogated recoveries for cyber claims are not without their difficulties where parties are effectively navigating uncharted territory.

Wotton Kearney has significant experience in handling subrogated claims following cyber incidents. We set out some of the critical issues which must be considered where seeking to explore subrogated recoveries for cyber claims.

Forensic Investigations

Forensic investigations provide the roadmap for any recovery action and should identify how the incident occurred, what security measures were (and were not) in place at the time, and how the attack could have been prevented.

Forensic investigations will help flush out the key liability issues, such as whether appropriate steps were taken to secure the insured’s network and assist with the early identification of potential recovery targets. Working closely with forensic investigators during the claims process will also assist with clarifying the technical aspects of the incident, which are often critical in understanding how and why any purported wrongdoing of technology professionals caused or contributed to the incident.

Often there are multiple third-party service providers who perform separate but interrelated roles, and it is critical that any forensic investigation considers the involvement of any network and data providers, managed service providers, antivirus software vendors, software installation services and ad hoc break/fix IT services.

Early identification of potential recovery targets through forensic investigations will also allow insurers to determine the viability of any recovery action at an early stage by considering whether the recovery target is based overseas, was also a victim of the incident, and/or is uninsured for its losses and any liability to third parties.

Terms of Engagement

The nature of any formal contract between an insured and recovery targets is often a determining factor in any recovery action.

If a written contract does exist, insurers will need to determine:

- who is responsible for managing cybersecurity, configuring data backups or patching software vulnerabilities, and

- does the contract purport to limit or exclude liability? If so, do the terms give rise to legal arguments around unfair contract terms and consumer protection laws?

Where there is no written contract or agreement, recovery becomes more difficult as insurers will need to prove the existence of the contract (either by conduct and/or orally) by relying on other evidence of cybersecurity obligations performed, or services provided more generally.

Causation

Recoveries against technology professionals are typically founded in negligence, breach of contract, and/or misleading or deceptive conduct in respect to the technology professional’s systems or competency.

This raises an associated issue of causation, where the increasing sophistication of threat actors poses real questions as to the ability of third-party providers to prevent a cyber-attack in any event.

Another factor which is often prevalent in cyber recoveries is determining whether factors outside of the control of the recovery target have contributed to the loss sought to be recovered by insurers. Common examples of this are poor record management, shared responsibility for maintaining computer systems/updates, delays in responding to incidents, and where business interruption/loss is claimed, the nature of the communications sent by the insured to its clients.

The evolving landscape of cyber threats and the legal intricacies surrounding them require insurers to adapt and refine their strategies to navigate these complex cases effectively, particularly as cyber-attacks can occur simultaneously along multiple aspects of the same technology supply chain.

The ability for an insurer to squarely attribute liability for an incident where there are multiple parties involved is a highly complex undertaking well-illustrated in the Singaporean High Court decision in Razer v Capgemini [2022] SHC 310 and the subsequent appeal (Razer Decision).

Razer Decision

In the third issue of our Cyber, Tech and Data Risk Report, we discussed developments in the trial between American-Singaporean gaming hardware manufacturer Razer and IT vendor Capgemini over a 2020 data breach.

In December 2022, the Singaporean High Court awarded Razer $6.5 million in damages including $6.1 million in loss of profits from Razer’s e-commerce platform, along with additional costs for engaging a law firm and a forensic expert.

Capgemini filed an appeal of the High Court’s decision and argued that it should only have to pay “nominal damages” instead of the $6.5 million awarded at first instance.

During the appeal hearing, Capgemini’s lead counsel argued that Razer:

- failed to prove damages for loss of profit

- did not adequately mitigate its losses by delaying response to warnings, and

- should be considered contributorily negligent for the delay.

Capgemini claimed that Razer’s cybersecurity and compliance process architect did not take reasonable steps to address the data leak. They highlighted Razer’s admission that its process architect had failed to respond immediately and escalate warnings received from Capgemini.

Capgemini pointed out that Razer had issued a warning letter to its process architect, emphasising that the extent of the issue could have been significantly reduced if she had responded appropriately. However, the judge did not consider the letter to be significant in determining contributory negligence.

Razer’s lead counsel questioned the extent of delay that would constitute a breach and one of the judges on appeal expressed concern over Razer’s failure to promptly respond to the warnings and questioned why contributory negligence should be considered zero. Razer agreed that there was a delay but argued that they were not negligent overall.

The Court directed both parties to discuss a possible reduction in damages if contributory negligence or failure to mitigate on Razer’s part is established. The court otherwise reserved its decision.

The case highlights the complexities in attributing liability to external and internal technology professionals in circumstances where both parties have a part to play in data breach response. The extent to which the Court considers Razer contributed to its own negligence by reason of the delay to respond to warnings issued by Capgemini will prove telling for future cases concerning contributory negligence allegations in technology professional claims.

1Cyber Threat Report, Australian Signals Directorate, 14 November 2023, 2.

New Zealand

In September, the Privacy Amendment Bill 2023 was introduced to Parliament. The Bill, which amends the recently adopted Privacy Act 2020 fills a “gap” in the current regulation in circumstances where agencies collect personal information indirectly.

The Privacy Act 2020 requires agencies provide certain information to individuals when collecting personal information directly (under Information Privacy Principle 3 (IPP3)). This includes information about the collection, what the information may be used for, and the individual’s rights under the Act. In a bid to bolster transparency and individual privacy rights, the Bill extends the notification requirement to collection of personal information indirectly, or from sources other than the individual in question.

The Bill imposes this requirement through a new information privacy principle – IPP3A. As with IPP3, IPP3A requires that individuals are notified of: the collection and the purpose of it, the intended recipients of the information, details of the agency collecting and/or holding the information, if collection is authorised or required by law, the particulars of that law, and the individual’s rights to access and correct the information.

As with IPP3, there are exceptions to the IPP3A requirements. These include where the information is publicly available, or the individual has already been made aware of the information referred to in the notification.

When the Bill is passed into, law agencies will need to assess their notification practices and ensure that they are complying with the Privacy Act 2020 when collection personal information from individuals and third party/indirect sources.

On 31 July, the Government released a 2022 report from the Cyber Security Advisory Committee (CSAC), which sheds some light on the future of the Government’s role in cyber incident response in New Zealand.1 The CSAC made sweeping recommendations which included:

- creation of a ‘single front door’ agency for notification of cyber incidents and coordination of response resources

- implementation of minimum cyber risk management guidelines for New Zealand companies

- introduction of mandatory reporting of cyber incidents and ransom payments in specified industries/sectors

- an oversight regime for ISPs and MSPs, including mandatory cyber incident reporting requirements

- a review of the cyber insurance market led by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, and

- direct intervention to strengthen the cybersecurity labour market through migration, training and working with education providers.

At this stage, the Government has proceeded with just one of the CSAC report’s recommendations. On 31 August 2023, CERT NZ was folded into the GCSB, with then GCSB Minister Andrew Little confirming that an improved operation model will take effect in 2024. This appears to be the first step towards the creation of a “single front door”, with the intention of streamlining the Government’s outreach and assistance to entities impacted by cybercrime. In the meantime, CERT NZ and NCSC will continue to deliver existing functions. We await the Government’s next steps in this area with great interest.

Of note are the CSAC’s comments of the state of cyber insurance in New Zealand, in particular the under-insurance of New Zealand businesses when it comes to cyber incidents. Given the change in Government since July, it remains to be seen whether the remainder of the CSAC’s recommendations will be implemented.

In September this year, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) launched a project on children and young peoples’ privacy rights.

The OPC is currently seeking input from professionals who work with, and advocate for, children. Input will then be sought from the wider community, including children, in early 2024.

The Privacy Act 2020 contains specific requirements addressing the collection of information of, from and about children and young people, although these are relatively limited. The OPC’s currently project seeks to assess the effectiveness of these requirements to establish if further guidance is required.

This latest project coincides with a recent statement from OPC regarding reports of schools considering deployment of CCTV in school bathrooms to combat negative behaviour such as bullying and vaping. The OPC did not advise against this action but recommended that schools conduct a privacy impact assessment to ensure all relevant considerations are engaged with, including less intrusive options.

The announced project and recent commentary reflect a clear focus on children’s privacy for 2024. Whether this results in amendments to the Act, or more formal guidance or regulation around processing of children and young people’s information, remains to be seen. Agencies dealing with children and young person’s personal information would be well advised to keep a close eye on any output from the OPC in this area, which we will continue to provide updates on.

Following various regulatory and legislative developments overseas, and the release of a preliminary practice note in May, the OPC has released its formal guidance on the use of AI and the application of the information privacy principles (IPPs).1

The guidance starts by setting out a limited number of technologies (or descriptions of technologies) that the OPC considers to be “AI” for the purposes of the advice. It goes on to detail the ways these technologies may engage the Privacy Act 2020 and how entities may utilise AI responsibly.

Of particular note are the OPC’s expectations for agencies using AI, which include:

- approval of senior leadership based on full consideration of risks and mitigations

- consideration of whether a generative AI tool is necessary and proportionate given potential privacy impacts and consider whether you could take a different approach

- completion of privacy impact assessments before a tool is used

- transparency – informing individuals how, when and why a tool is used

- engagement with Māori around potential risks and impacts to the taonga of their information

- procedures to ensure accuracy of, and access to, information

- human review prior to acting on AI outputs to reduce risks of inaccuracy and bias, and

- adequate controls over retention and disclosure of information by AI tools.

The latest guidance document acknowledges the recent rise in generative AI, which has driven an upswing in guidance and regulatory scrutiny. Given the sudden but seemingly sustained take-up of these technologies, we anticipate that the guidance note will be the start of regulation and guidance in this area, rather than the finished article. For the meantime, the guidance represents a robust and considered starting point for those considering the adoption of AI tools. If you are considering adopting AI tools and have any queries, do reach out to a member of WK’s Cyber, Privacy & Data Security team to discuss.

WK is pleased to be ranked for data protection for the very first time in Australia and New Zealand in the 2024 Chambers Asia-Pacific legal rankings.