By: Amanda Beattie, Dylan O’Keefe and Tess Jenks

Introduction

The class action regime in Australia has changed dramatically in the last couple of years. Our “ones to watch” series tackles a series of topics to explain the regime’s current state, highlight recent developments and flag issues that should be on the radar for the Australian and international insurance markets and their insureds.

Our first paper in the series focuses on multiplicity.

At a glance

- Multiplicity has been described as a “plague” and a “nonsense” by Federal Court judges and even led one judge to question whether there are innovative solutions to address the issue, including an order preventing the filing of multiple actions. Whatever the description, multiplicity is certainly a challenge for courts and one that is unlikely to be easily resolved.

- There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to the progression of multiple proceedings, and while the need for a hearing in relation to carriage contests adds to the time and cost for all parties, a carriage dispute may present an opportunity for defendants to obtain additional information to assist with strategic considerations at the start of a proceeding.

The issue

The competing action is not a new phenomenon in the class action landscape. It was the subject of much discussion following the 2021 High Court decision in Wigmans1, which confirmed the “beauty parade” approach to resolving the issue and, as was predicted by many following the decision, the number of competing actions has increased in the last couple of years. This year, there have been more than 17 competing class actions filed against 7 defendants.

How courts approach the issue

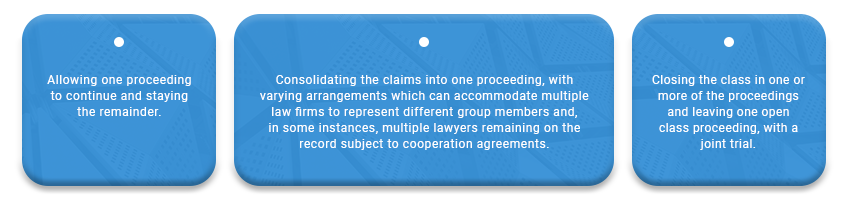

Courts can resolve the issue of competing class actions in a number of ways, including:

The High Court in Wigmans stressed that multiplicity of proceedings is not to be encouraged, but there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to resolving the question of how the claims should be progressed. The Federal Court and the Victorian Supreme Court have issued guidance for dealing with competing class actions. Taken together, the following factors are relevant to the question of competing claims:

- the funding proposal, cost estimates and potential returns to group members

- security for costs proposals

- the nature and scope of each of the pleadings

- the size of classes

- the extent of any bookbuild

- the experience of plaintiff lawyers, funders and available resources, and

- the progress and conduct of the proceedings to date.

The first action to file does not immediately take priority, and courts have stressed that in carriage contests, although a delay in filing may be relevant and judges may take delays into account. Earlier this year, the second action filed against Medibank was stayed by Beach J pending carriage, which generated extensive attention and commentary given it appeared to favour the first to file, although in reality was more likely a pragmatic approach.

Multiplicity – what have the recent cases shown us?

This year has seen competing actions in a range of matters including shareholder class actions (Star Entertainment and Downer EDI), consumer actions (Medibank and Kia/Hyundai), the AFL concussion actions and KFC rest break actions. The majority of these are in the Victorian Supreme Court, which is due in large part to the availability of group costs orders (GCO) in Victoria, which we will consider in more detail in a further paper in this series. In dealing with these matters, a number of interesting questions have been raised by the courts.

Competing funding proposals

Where the class actions are competing in the Victorian Supreme Court, the question of multiplicity and the question of funding, including whether a GCO should be made, go hand in hand. This is because the funding proposal can be a key consideration (among many) as to which proceeding should be allowed to continue, because it is directly relevant to potential returns to group members.

The four-way carriage contest in the Star Entertainment proceedings highlighted the extent of competition and debate that can occur regarding different funding proposals in a carriage contest. The four proposals were:

- Slater & Gordon – GCO 14%

- Phi Finney McDonald – GCO 17%

- Maurice Blackburn – ratcheted GCO (10% to 25% depending on return to group members), and

- Shine – no win, no fee with a 25% uplift on their professional fees.

Each of the firms proposing GCOs were critical of Shine’s proposal, which was incidentally also the last action filed, arguing it afforded less protection for group members in terms of cost blowouts. Others questioned the low GCO rate proposed by Slater & Gordon (prior to this decision, all approved GCOs have exceeded 20%), suggesting it could lead to a lack of resources being committed and potentially undermine the purpose of the GCO provisions (i.e. the recovery at that rate would be uneconomical for law firms).

In determining which proceeding should continue, the court noted that while there were a number of issues raised during the hearing, the substantive difference between the proposals concerned the approach to funding. The court noted that the proposals were finely balanced but ultimately found that the more attractive funding proposal (being Slater & Gordon’s) should carry weight in the evaluative exercise.2

In the Downer EDI carriage contest, similar argument as to the “economics” of the funding proposals were raised. In that case, it was submitted that rival firms are exposing themselves to financial risk to achieve a lower funding arrangement and carriage of the claim. Courts have historically rejected these arguments, instead focusing on the experience of the firms and their ability to litigate the cases “in a manner consistent with the overarching obligations in the Civil Procedure Act”.3

What is clear from the decisions is that the funding proposal, while not solely determinative, will continue to be a significant factor in carriage disputes and we can expect to see GCOs being made for under 20% going forward. The courts are also likely to take a strict approach to the implementation of the funding proposals put forward during carriage motions. Just this week, in a settlement approval hearing, Murphy J warned that absent exceptional circumstances, a firm or funder that succeeds in a carriage motion should not expect to receive anything more than was proposed as part of that application.4

Multiple proceedings filed in different courts

The filing of proceedings in different jurisdictions, usually the Federal Court and the Victorian Supreme Court, adds complexity to the issue. In another example of a four-way contest, three proceedings against Downer EDI were filed in the Federal Court between March and June this year and a fourth was filed in the Victorian Supreme Court in May. A similar situation played out in actions against Kia and Hyundai, where proceedings were filed in the Victorian Supreme Court in January and in the Federal Court in May.

In both cases, there were joint case management hearings before a judge of each court. In Downer, after some back and forth, the applicants in each of the Federal Court proceedings elected to request a transfer to the Victorian Supreme Court, allowing for a hearing before a single judge. In Kia/Hyundai, the applicants in the Federal Court sought to transfer to the Supreme Court but argued carriage should be addressed first because it could make the transfer application redundant.

At the joint case management hearing in the Kia/Hyundai matters, the judges formed the view that the transfer application should be dealt with before the question of carriage, as a joint sitting to hear a substantive motion, such as carriage, would be complex and should be avoided if possible. In both cases, the courts ordered the transfers to the Supreme Court to allow the carriage motions to be heard before a single judge, which is due to be heard later this month.

Appointment of contradictors – a second pair of eyes for the court

Contradictors have been used by the court in an array of contexts, with the court in The Star hearing appointing a contradictor to independently assess the funding proposals. Having considered each of the firms’ proposals, the contradictor concluded they were all well-supported and that the court could form the view, despite suggestions to the contrary, that each firm had the means to fulfill their obligations under their respective proposals. In terms of the specific funding proposals, the contradictor indicated that the Slater & Gordon and Maurice Blackburn proposals were hard to separate and, in doing so, His Honour rejected the submissions that the Slater & Gordon rate was too low. On balance, the contradictor endorsed the Slater & Gordon proposal, but said it was a difficult recommendation to make.

Regulatory investigations and their effect on litigated claims

The class actions filed in relation to the 2022 Optus and Medibank data breaches have raised a number of interesting questions, including in relation to multiplicity. Not only have competing actions been filed in the Federal Court (in respect of Medibank), but the class actions overlap with the representative complaints lodged by plaintiff firms with the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), which has the power to order compensation.

This presents a new challenge for courts – one that is even more difficult to resolve given the OAIC are not a party to the class actions. At case management hearings in both Medibank and Optus in August, Beach J questioned the defendants about the progress of the OAIC investigations. In the Optus matter, His Honour made an order requiring the OAIC to appear at a hearing to explain the delay in resolving the complaints. His Honour offered to make the same order in the Medibank proceedings, but counsel for Medibank indicated the OAIC had promised a response to its request to have the investigations discontinued.

Recent developments saw Medibank urge Beach J to restrain the OAIC from making a determination in the representative claim because there is a risk of an interference with the administration of justice should the Court and the OAIC have inconsistent findings. In seeking the order, Medibank made it clear that it was not attempting to restrict the OAIC from investigating on its own initiative circumstances which are outside the scope of the Federal Court proceedings’ claims that could result in other findings of public interest. The applicants in the proceeding supported Medibank’s application and stated that the progress of the OAIC investigation and determination was unsatisfactory. Counsel for both the representative claim and the OAIC argued that inconsistent findings between the Court and OAIC is not reason enough for the restrictive order. Beach J reserved his decision.

Implications for defendants and insurers

For the most part, multiplicity is the domain of the plaintiff firms, but the courts have noted that where a proposal to resolve a multiplicity problem affects the defendant differentially, its interests are also relevant. Notwithstanding that, there are still some important considerations to bear in mind:

- The need for a hearing in relation to carriage adds to the time and cost for all parties, albeit more limited costs for defendants. However, it may provide defendants with additional time and information (see below) to assist with strategic considerations at the start of a proceeding. However, the court will not always resolve competing actions first. In the KFC rest break class actions, the Federal Court recently ordered the parties to file defences in both claims before determining carriage, in order to clarify the contested issues and resolve the issue of whether there are appropriate separate questions to be determined.

- A carriage dispute can be a potential opportunity to obtain more information in relation to the claim, including the make-up for the class. The type of information that could be obtained depends on what the court requires from the plaintiff firms in respect of carriage and the court may also restrict defendants’ access to certain information. To the extent that information is obtained at this stage of the proceedings, it can assist defendants and insurers to better understand the potential liability at an earlier stage of the proceeding than it might otherwise be able to.

- There may also be an opportunity for defendants to take a pragmatic approach at an early stage of proceedings if there are differences in the scope of the pleading or group member definitions in competing class actions. That was the case in The Star hearings earlier this year, where The Star indicated a preference for two of the proceedings on the basis that they would provide greater certainty in the outcome of the proceedings.

Given the volume of proceedings being filed and the increase in competition between plaintiff firms, we expect to see this issue remain at the fore for some time, particularly given the different approaches courts have taken depending on the circumstances of each case.

[1] Wigmans v AMP Limited [2021] HCA 7

[2] DA Lynch Pty Ltd v The Star Entertainment Group Ltd [2023] VSC 561

[3] Lidgett v Downer EDI Ltd [2023] VSC 574

[4] Ghee v BT Funds Management Limited [2023] FCA 1553