At a glance

- Class actions following large-scale data breaches have been filed for the first time in Australia, adding a further layer of complexity to the management of cyber incidents.

- There are potential obstacles to the success of such class actions, and it is not yet clear if they will be a viable (or best) means of recovering damages for individuals affected by those data breaches.

- The absence of definitive guidance on the standard of conduct required in relation to cybersecurity and data enhances the challenges parties face in these novel claims.

- Robust cyber resilience and risk mitigation measures, proactive cyber readiness, and sound privacy and data practices remain the best defence, particularly as these practices will be under close scrutiny following a data breach and in any subsequent litigation.

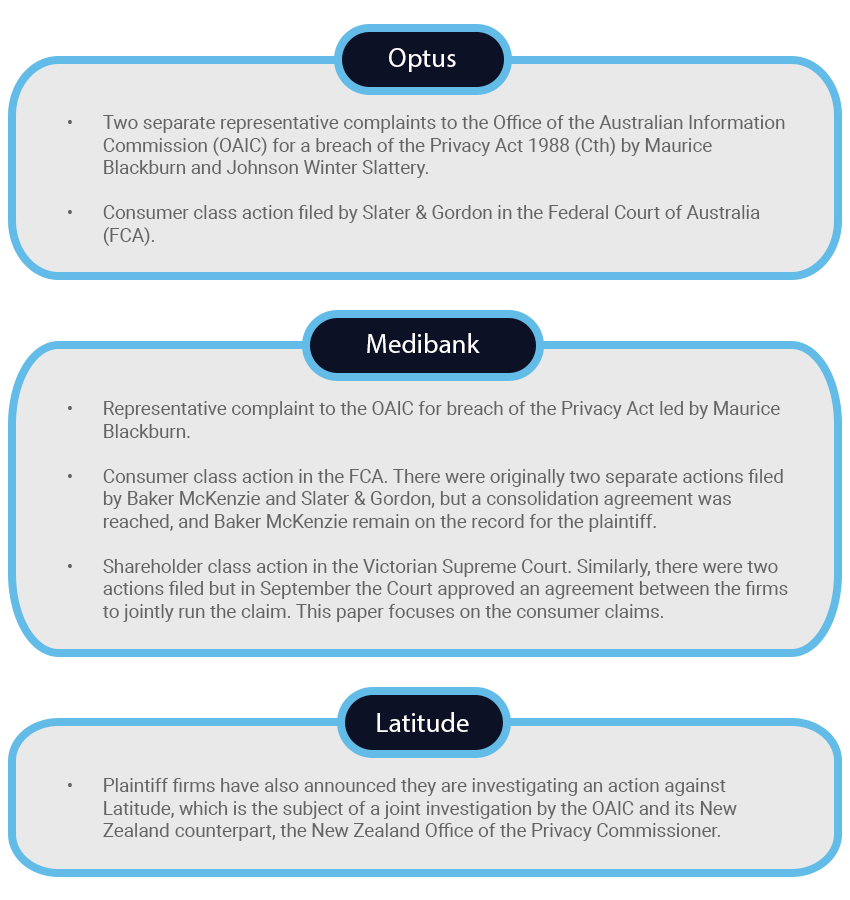

The current actions

Anyone casually glancing at the Australian news in the past 12 months would have noted the frequency of high-profile cyber incidents involving the theft of significant personal information of millions of Australians. Following fast on the tail of these breaches has been a new legal development – the initiation of class action litigation as a means of seeking compensation for affected individuals.

Competing actions – a twist on the multiplicity issue

While there were competing class actions filed in respect of the Medibank breach, they were ultimately resolved by consent without the need for a hearing. The multiplicity issue arises as a result of the ongoing OAIC representative complaints.

The OAIC provides an alternative path for plaintiffs seeking recovery in a privacy breach. The Privacy Act also allows for representative complaints to be made where there’s an allegation of interference with the privacy of a number of individuals. Once a complaint is made, it is at the discretion of the OAIC whether it is investigated. If an investigation proceeds, it can ultimately result in a determination being made by the Privacy Commissioner, including as to the amount of compensation to be paid to affected individuals.

Complaints of this nature were made to the OAIC in relation to both the Optus and Medibank breaches before class actions were filed. The existence of these complaints has been a contentious issue in the class actions, which has resulted in the Court taking an approach similar to that which it would take where competing class actions have been filed. At an early stage in the Medibank proceedings the Court indicated that it expected Medibank would apply to the Commissioner to discontinue the representative complaint investigation. The issue has come to a head with Medibank seeking an injunction to prevent the OAIC from continuing its investigation. The hearing in relation to that issue is currently listed for 10 November 2023.

In the Optus proceedings there is the added complication of there being multiple OAIC complaints. In August, the Court ordered the OAIC to appear at a hearing to try and resolve the issue. Two days before that hearing, the applicant in one of the complaints filed an application for judicial review of the OAIC’s decision to accept the other, which was heard on 18 October. Judgment is reserved.

The decisions on these issues will provide interesting insight into how the Court approaches this unique multiplicity debate.

Why hasn’t there been class actions in this space before now?

Class actions resulting from data breaches have long been considered possible, but a significant hurdle to overcome has been what cause of actions are available to individuals impacted by a data breach.

The Privacy Act does not currently provide individuals with a direct right to seek compensation where organisations breach the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) when handling their personal information, and there is no other enforceable right of action for breach of privacy in Australia. As such, there is no obvious civil cause of action that an individual might bring when a data breach occurs. As has been well-publicised, this may be a temporary state of affairs; the introduction of a direct right of action to permit individuals to apply to the courts for relief following an interference with privacy was proposed in the Privacy Act Review Report (Report).1 The Report also recommended the introduction of a statutory tort for serious invasions of privacy.2

The Government announced in principle agreement to both a direct right and statutory tort in its response to the Report, which was released on 28 September 2023 (Response).3 However, it remains to be seen whether the introduction of those measures will increase the viability of class actions in response to data incidents.

Direct right

The Response agrees that individuals should have direct access to courts to seek remedies for breaches of the Privacy Act, but a prerequisite to taking that step is a complaint being lodged with the OAIC. It would only be if there was no reasonable likelihood of resolution of the complaint or it was assessed as unsuitable for conciliation that an action could be commenced in Court. As noted above, under the current legislation individuals can lodge complaints with the OAIC, but the reforms would require that step to be taken before any proceedings relying on the new direct right could be commenced.

This two-step process could discourage class action proceedings from relying on breaches of the Privacy Act by adding an additional layer of to the process, which would not impact other claims, for example breach of contract or misleading and deceptive claims which are part of the current class actions.

Statutory tort

The statutory tort for invasion of privacy would apply in situations where there has been serious intrusion into seclusion or a serious misuse of private information. In order to establish a cause of action, individuals would need to prove:

- the invasion was serious

- they had a reasonable expectation of privacy

- that the invasion was committed intentionally or recklessly, rather than being the result of negligence, and

- that the public interest in privacy outweighs any countervailing public interest.

The elements of that claim do not clearly lend themselves to the factual scenario that arises in most large-scale cyber related data breaches for a couple of key reasons:

- it is the threat actor, rather than the organisation, that has invaded the individual’s privacy. There is an argument that the organisation permitted the invasion, but whether that is a sufficient basis to bring an action remains to be seen, and

- even if an action could be commenced against an organisation on the basis that it permitted the invasion, it would be difficult for a plaintiff to establish an intention on the part of an organisation to permit the invasion of privacy. The more likely avenue would be establishing that an organisation was reckless to the risk but that would still be high threshold for a plaintiff to prove.

Notwithstanding the potential difficulties in applying these new causes of action to data breach class actions, we expect to see plaintiff firms seek to take advantage of them if they are introduced. The response from defendants and, ultimately the Courts, will determine whether they are viable in class actions.

How the current claims have been framed

The applicants in the current claims have relied upon a mix of the following causes of action:

- Misleading and deceptive conduct, potentially on the basis of breach of a privacy policy or other representations about the management of data (an avenue successfully pursued by the ACCC against Google)4

- breach of contract, including terms and conditions relating to how the companies would deal with personal information and in relation to the privacy obligations owed to group members

- breach of confidence, linked to allegations that the defendants retained data longer than required, and

- negligence, arising from a failure to take sufficient precautions to protect personal information.

The relief sought is not limited to financial compensation and includes mandatory injunctions requiring the destruction or de-identification of customer data on the basis that the defendants failed to comply with various obligations, including under the Privacy Act. This alone is a very significant development from a corporate IT management perspective; complying with these orders could be extremely complex and costly (over and above any compensation order made), particularly where legacy IT systems are involved.

The challenges of establishing a breach

One of the misperceptions that arises following a data breach is that it must be the result of a failing on behalf of the company, but it is not that clear cut. One of the fundamental obstacles to claims is the difficulty of establishing that there is a legally recognised standard of conduct in relation to cybersecurity or data management that the organisation in question has breached and, most importantly, that it was this breach which has resulted in the loss the individuals have suffered.

At the heart of this, is that there is no prescribed, legal requirement mandating particular levels of cyber defences or data management. There is principles-based guidance, designed to evolve with technology over time or apply differently to different organisations, but that makes framing a claim inherently difficult. This will inevitably result in a “battle of the experts”, adding significant costs to the proceedings.

It will be interesting to see how this aspect of the claims against Medibank and Optus develop following discovery by the defendants, which will likely result in the disclosure of information relevant to establishing breach. In Optus, this issue has already come to the fore in light of a debate about the privilege status of a report Optus obtained from Deloitte following the data breach. Optus maintains the report is privileged, but reference to it in a press release has raised questions as to whether privilege can be maintained. The report was the subject of submissions before the Court on 14 September and the decision is reserved.

Is there a recognised loss to be recovered?

Even where a cause of action can be made out, the key issue with these claims will be establishing compensable loss that was suffered by the group members.

If a determination of loss is made by the Court in these cases, it will be the first time loss has been judicially recognised for claims of this kind. There have been earlier attempts at establishing loss through a class action following a data breach, although not of the size and scale of the current matters. In Evans v Health Administration Corporation [2019] NSWSC 1781, a claim was made on behalf employees and former employees of the defendant following the unlawful access and sale of personal information of those employees by a contactor of the defendant. The plaintiff’s claim included allegations for breach of confidence, breach of the employment contract and misleading and deceptive conduct. The proceedings settled, but in approving the settlement (around $2,400 per group member) the Court noted the risks associated with this kind of claim, including “the need to establish new ground in relation to some of the claims sought to be pressed in this jurisdiction.”5

The challenge for the plaintiffs is the need to demonstrate that they have suffered damage directly as a result of the data breach. The current claims seek a range of relief, including damages and equitable compensation. There are a number of difficulties that plaintiffs face in establishing both economic and non-economic loss, particularly due to the requirement for an assessment of the circumstances of each individual.

Economic loss

- The time and cost of arranging replacement documents and reinstating relevant security protections. Generally, companies offer to compensate customers for some of these costs, which means that any additional claim needs to be over and above those costs already covered. That gives rise to questions of remoteness and causation depending on how quickly group members act and what steps they take, including a question of whether those steps were required, because of the data breach. The question of whether an individual can be compensated for their time associated with taking such steps may also be a consideration but presents added difficulties in terms of quantification.

Non-economic loss

- Emotional distress or mental anguish and trauma. This has traditionally been difficult for plaintiffs to establish and even more so in a claim where the cause of action is novel. The plaintiff in the Medibank claim, for example, alleges that the extraction of their data and the publication of it on the dark web, caused distress, embarrassment, and anxiety. Those are matters which would ultimately need to be the subject of expert evidence. Further, the impact on each individual is likely to differ depending on their person circumstances; the disclosure of an address may have little impact on certain individuals but cause considerable distress for others, for example a victim of domestic violence. Damage of this kind could also take years to materialise and have ongoing impacts and as it presently stands the apprehension or risk of such loss is not compensable by itself, except to the extent it can be recovered by emotional distress.

These are matters which make it difficult to make a global assessment of damages for individuals, which is not only an issue for the Courts to grapple with, but also the parties as part of any settlement negotiations. It is too early to say whether we will see an assessment of these issue by the Court in the current claims. Given the inherent difficulties in providing the allegations and the risk of creating a precedent for the defendants, a settlement of the claims would not be surprising.

What’s next?

- Clarity on the status of the OAIC representative complaints against Optus and Medibank.

- Reforms to the Privacy Act – the Federal Government has committed to introducing the legislation in 2024, although given the new causes of action have only been received in principle agreement at this stage, they could take longer to be introduced than other reforms.

- Potential for new actions, notably Latitude which is under investigation. We could also see further claims for less publicised incidents if the current claims are successful in obtaining a positive outcome for group members.

- An outcome in the current proceedings, whether by mediation or judgment, has the potential to change the landscape of these claims.

- ASIC has recently indicated that it is prepared to commence proceedings against companies and directors in cases where it considers reasonable steps were not taken to protect against the risks of a data breach. The outcome of ASIC investigations and subsequent proceedings could present another avenue for class actions in relation to these issues.

[1] Proposal 26.1 Privacy Act Review Report, https://www.ag.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-02/privacy-act-review-report_0.pdf.

[2] Proposal 27.1

[4] https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/google-llc-to-pay-60-million-for-misleading-representations

[5] Evans v Health Administration Corporation [2019] NSWSC 1781 (12 December 2019) at [44]